Your network is your net worth.

-Porter Gale

In many ways we have come full circle with the structure of provider networks over the past several decades. We have gone from employer sponsored health plans providing unrestricted access to providers, directing care within a managed network through a gatekeeper, using benefit differentials to steer utilization to a network of providers, and now with costs continuing to spin out of control many new variations exist. The goal? To lower health care costs that continue to drastically outpace general inflation and other economic measures.

The crux of the problem is nothing new. Beyond market forces and the innovation of employer groups, consultants, health plans and technology, the federal government has even addressed the need for change in the healthcare delivery system at several degrees of magnitude. The Health Maintenance Organization or HMO was given federal support with the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973, removing restrictions and encouraging expansion. Initially the intent was for employers to provide a more comprehensive benefit package at a lower cost. What’s not to like about that, don’t we all want this from our employer sponsored health plans? As the concept advanced, primary care centric medicine made sense even without the connectivity we have today. Due to continued cost pressures along with conflicted and bloated health plan administration, however, the end of the 20th century saw many of these plans fail. The acronym for many has since become synonymous with restricted access to providers. Additionally, the proverbial fox watching the henhouse, with the health insurance carrier and the providers being one in the same.

So what were we to do next? Overcorrect. The Preferred Provider Organization or PPO that started in the early 80’s with Taft-Hartley plans gained tremendous momentum with others as many employer groups moved out of HMO’s, particularly across the western part of the United States. The PPO was attractive because it technically provided access to most providers. Those providers that adhered to a negotiated rate schedule were rewarded with higher patient volume through benefit plan design steerage. Conceptually the higher patient volume outweighed the lost revenue per episode that non-network providers may charge. Over time this fee for service model pressured the provider community because it took the focus away from quality and shifted it to quantity. Even more simply, providers were just not able to spend much time with patients whether by necessity or human nature.

While the PPO still remains the most popular network choice for many plan sponsors, the value of the network discounts has come into question. In particular, the basis for determining the negotiated or discounted rate. For example, would you rather have 50% off of $1,000 or 10% off of $500? The networks negotiating these rates keep most of this information confidential, so we as consumers are left in the dark. They are then free to promote their leverage in the marketplace and corresponding overall “deep” discounts off billed charges which can essentially be any starting number. To combat this some plan sponsors have implemented Referenced Based Pricing (RBP) models that reimburse a percentage of a cost basis, or reference, such as a percentage of the Medicare allowable rates. While simple in concept and intuitive in design, there has been some resistance by the facility and provider community resulting in limited expansion of these plans. Economic, political and social factors have come into play as is often the case with the tremendous amount of money spent on healthcare.

With the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which just celebrated its 10th birthday, so came the genesis of today’s Accountable Care Organization or ACO. In its simplest form the ACO resembles the HMO, but with today’s network technology to share data and a shift to measuring outcomes through quality metrics. The ACO combats the excessive fee-for-service model by compensating providers on meeting these metrics, many with a shared savings component although the measurement and reporting remains a challenge given the complexity involved. From an underwriting perspective there may not be much if any short-term cost savings since ultimately the providers and facilities will tend to negotiate payments on an overall revenue neutral basis. Over time, however, if quality improves then the costs should decrease. The ACO model is typically more provider centric although most are now run by large healthcare facilities and/or insurance carriers. Will these organizations take a pay cut through reduced utilization over time? I’ll leave that for you to ponder.

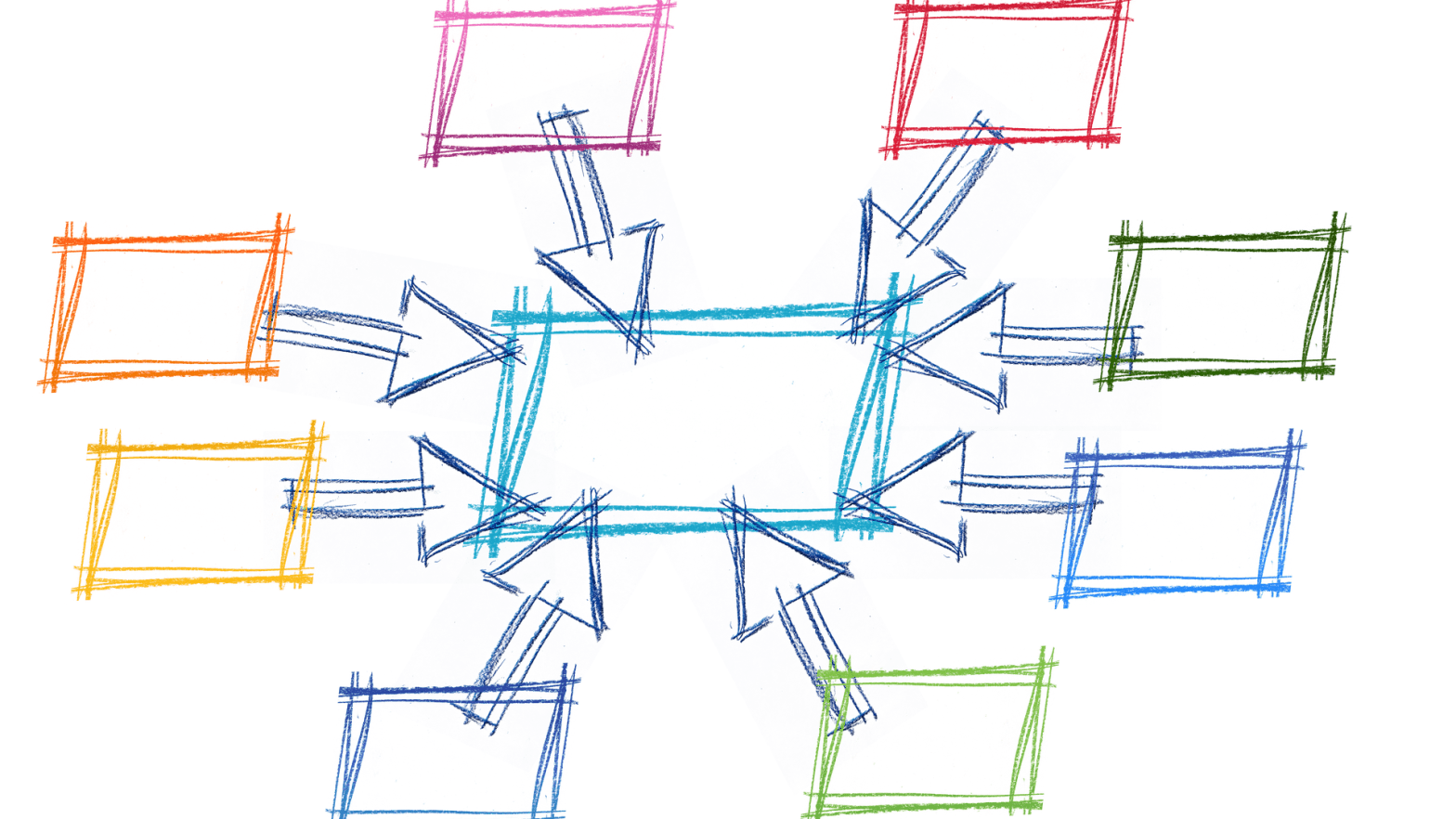

Variations of “performance” networks have evolved out of the ACO model. From Clinically Integrated Networks (CIN) that are provider led and aimed at improving care and lowering costs, to “narrow” networks that may simply be more tightly controlled PPO’s driving deeper discounts that may or may not have a quality measurement component. The latter is typically recommended if seeking reduced utilization over time since we are often unable to look at the discount methodology found in provider contracts as stated earlier. In all cases there remains significant exposure to health plans (and members) when services are provided out-of-network. So much exposure, and a significant source of revenue for the same companies that negotiate the in-network rates, that I will cover this topic in a future article. Until then I’ll echo my continual support for self-funding and the plan sponsor fulfilling their fiduciary role by selecting TPA’s, networks and other service providers that are transparent and free of internal and external conflicts of interest.